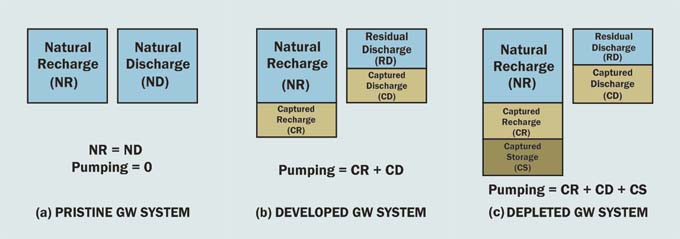

Fig. 1 Recharge and discharge in groundwater systems.

|

Sustainable Yield of Ground Water

By Victor M. Ponce1

Introduction

Water occurs both on the surface and under the surface of the Earth. The surface water and

the ground water are both part of the hydrologic cycle. Surface water can become ground water

through infiltration, while ground water can become surface water through exfiltration. Therefore, surface water and ground water are

inextricably connected; one cannot be considered or evaluated without regard to the other.

Surface water and ground water can be

shown to differ in two important ways:

(1) surface water is completely renewable, usually within days or weeks, while ground water is not completely renewable, since it

may take decades, centuries, or even longer time to renew; and

(2) fresh surface water is scarce, particularly when compared with the large volumes of fresh ground water which are known to exist

below the surface.

With development pressures taxing the surface waters in many regions of the world, the trend has been to use ground water

to help resolve perceived surface water scarcities.

This paper examines the historical development of groundwater use and of the limits placed thereon throughout the years.

The concepts of safe yield and sustainable yield are reviewed. The traditional concept of safe yield, which equates safe yield

to annual recharge, is shown to be flawed because of its narrow focus. Sustainable yield extends beyond the conventional

boundaries of hydrogeology, to encompass surface water hydrology, ecology, and other related subjects.

Background

Excessive groundwater pumping can lead to groundwater depletion, and this may have serious social and economic consequences.

Attempts to limit groundwater pumping have been commonly based on the concept of safe yield, defined as the attainment and maintenance

of a long term balance between the annual amount of ground water withdrawn by pumping and the annual amount of recharge. This definition

is too narrow because it does not take into account the rights of groundwater-fed surface water and groundwater-dependent

ecosystems (Sophocleous 1997).

Recently, the emphasis has shifted to sustainable yield (Alley and Leake 2004; Maimone 2004; Seward et al. 2006). Sustainable yield

reserves a fraction of the so-called "safe yield" for the benefit of the surface waters. There is currently a lack of consensus as to what percentage of safe yield

should constitute sustainable yield. The issue is complicated by the fact that knowledge of several earth sciences is required for a

correct assessment of sustainable yield. Additionally, there are social, economic, and legal implications which have a definite bearing on the analysis.

At the outset, a distinction is necessary between pristine and non-pristine groundwater reservoirs. Pristine reservoirs are those that have not

been subject to human intervention; conversely, non-pristine reservoirs have a history of pumping.

In pristine reservoirs, average annual natural recharge, which is a fraction of

precipitation, is equal to average annual natural discharge, which feeds springs, streams, wetlands, lakes, and groundwater-dependent ecosystems.

Average annual recharge is normally taken over the period of record or some other suitably long period. Actual values of annual recharge may differ from the long-term average value.

Thus, net recharge, i.e, average annual recharge minus average annual discharge, is zero.

Three groundwater scenarios are possible:

(1) a pristine groundwater system, in equilibrium or steady state, in the absence of pumping;

(2) a developed groundwater system, in equilibrium or steady state, with moderate pumping at a fixed depth; and

(3) a depleted groundwater system, in nonequilibrium or unsteady state, with heavy pumping at an ever increasing depth.

In the pristine groundwater system, natural recharge is equal to natural discharge, net recharge is zero,

and pumping is zero. Thus, natural recharge equals natural discharge (Fig. 1 a).

In the developed groundwater system, captured recharge is the increase in recharge induced by pumping.

Likewise, captured discharge is the decrease in discharge induced by pumping. Then, residual discharge

is equal to natural recharge minus captured discharge. Net recharge is equal

to the sum of captured recharge plus captured discharge. Net recharge varies with the intensity of pumping; the greater the intensity of

pumping, the greater the net recharge. Pumping in the developed groundwater system is equal to net recharge, i.e., capture (Fig. 1 b).

In addition to captured recharge and captured discharge, the depleted groundwater system also features captured storage.

Net recharge is equal to captured recharge plus captured discharge. Pumping in the depleted

groundwater system is equal to net recharge plus captured storage (Fig. 1 c).

|

Fig. 1 Recharge and discharge in groundwater systems.

|

The greater the level of development, the greater the amounts of captured recharge and captured discharge, and, in the case of a depleted system, captured storage. The greater the captured discharge, the smaller the residual discharge. Since all aquifer discharge feeds surface water and evapotranspiration, it follows that intensive groundwater development can substantially affect local, subregional, or regional groundwater-fed surface water bodies and groundwater-dependent ecosystems. Historical Perspective

Lee (1915) defined safe yield as the limit to the quantity of water which can be withdrawn regularly and permanently without

dangerous depletion of the storage reserve. He noted that water permanently extracted from an underground reservoir reduces

by an equal quantity the volume of water passing from the basin by way of natural channels, i.e., the natural discharge.

To illustrate the existence of this natural discharge, Lee observed that heavy pumping would commonly result in the drying

up of springs and wetlands. Thus, he distinguished between a theoretical safe yield, equal to the natural recharge, and a

practical safe yield, a lower value which takes into account the need to maintain a residual discharge.

Theis (1940) recognized that all ground water of economic importance is in constant movement through a porous rock

stratum, from a place of recharge to a place of discharge. He reasoned that under pristine conditions,

aquifers are in a state of approximate dynamic equilibrium. Discharge by pumping is a new discharge superimposed on a

previously stable system; consequently, it must be balanced by: (a) an increase in natural recharge;

(b) a decrease in natural discharge;

(c) a loss of storage in the aquifer; or

(d) a combination thereof.

Theis distinguished between natural recharge and available recharge.

Available recharge is the sum of unrejected and rejected recharge. The unrejected recharge

is the natural recharge; the rejected recharge is the portion of available recharge rejected by portions of

an aquifer on account of being full (at least part of the time). To assure maximum utilization of the supply,

Theis argued that groundwater development should tap primarily the rejected recharge and, secondarily, the

evapotranspiration by non-productive vegetation. Thus, he defined perennial safe yield as equal to the amount

of rejected recharge plus the fraction of natural discharge that it is feasible to utilize.

Where rejected recharge is zero, the only way to replace the well discharge is by artificial recharge.

Kazmann (1956) argued that the concept of safe yield, when taken independent of considerations

of regional hydrology, is a fallacious one, because it cannot be reconciled with the legal doctrine

of appropriation. All water coming from the ground must be replaced by water coming from the land

surface in order for a perennial groundwater supply to be obtained. When all surface runoff in the

area overlying an aquifer has been appropriated, a perennial supply cannot be obtained from the ground

without encroaching on established rights. Echoing Theis (1940), Kazmann saw artificial recharge as an

effective technological fix to the safe yield quandary.

The concept of sustainable development emerged in the 1980s, forcing a reconsideration of safe yield practices.

Sustainable development must meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations

to meet their own needs (World Commission on Environment and Development 1987). Implicit within this definition

is the realization that natural resources could be exploited in an unsustainable fashion, i.e., in a way that

future generations will find it increasingly difficult to avail themselves of similar quantities of the same resources.

Thus, the intergenerational ethical dilemma.

Sustainability refers to renewable natural resources; therefore, sustainability implies renewability. Since groundwater

is neither completely renewable nor completely nonrenewable, it begs the question of how much groundwater pumping is

sustainable. In principle, sustainable yield is that which is in agreement with sustainable development. This definition

is clear; however, its practical application requires the understanding of complex interdisciplinary relationships,

which have only recently been examined.

Alley et al. (1999) defined groundwater sustainability as the development and use of ground water in a manner that

can be maintained for an indefinite time without causing unacceptable environmental, economic, or social consequences.

The definition of "unacceptable" is largely subjective, depending on the individual situation. For instance, what may

be established as an acceptable rate of groundwater withdrawal with respect to changes in groundwater level, may reduce

the availability of surface water, locally or regionally, to an unacceptable level.

The term safe yield should be used with respect to specific effects of pumping, such as water level declines or reduced

streamflow. Thus, safe yield is the maximum pumpage for which the consequences are considered acceptable.

Sophocleous (2000a) pointed out that the traditional concept of safe yield ignores the fact that, over the long term,

natural recharge is balanced by discharge from the aquifers by evapotranspiration and/or exfiltration into streams,

springs, and seeps. Consequently, if pumping equals recharge, eventually streams, marshes, and springs may dry up.

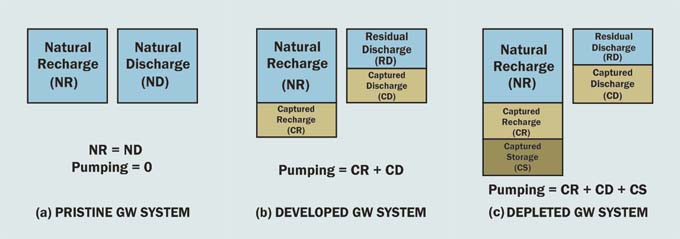

Additionally, continued pumping in excess of recharge may eventually deplete the aquifer. To illustrate, Sophocleous

presented two maps of perennial streams in Kansas, within the High Plains aquifer (Fig. 2). The latter map (1994) shows

a marked decrease in total length of streamflows in the western third of the state, within the elapsed period (1961-1994),

showing the impact of groundwater depletion on surface-water resources.

|

Fig. 2 Major perennial streams in Kansas: 1961 vs. 1994 (Sophocleous, 2000).

|

Alley and Leake (2004) recognized the dependence of yield on the amount of capture. Unlike natural recharge, which tends to be a constant for a given basin, capture is a function of the level of development; the greater the pumping, the greater the capture. Thus, capture could not be sustainable in all cases. There is concern about the long-term effects of groundwater development on the health of springs, wetlands, lakes, streams, and estuaries. Sustainability is seen as all-encompassing, addressing issues across the disciplines. Maimone (2004) argued that if sustainable yield must be all-inclusive, the idea that there exists a single, correct number representing sustainable yield must be abandoned. Instead, he proposed a working definition, coupled with an adaptive management approach, based on the following components:

Seward et al. (2006) found serious problems with the simplistic assumption that sustainable yield should equal recharge. In many cases, sustainable yield will be considerably less than average annual recharge; therefore, the general statement that sustainable or "safe" yield equals recharge is incorrect. Natural recharge does not determine sustainable yield; rather, the latter is determined by the amount of capture that it is permissible to abstract without causing undesirable or unacceptable consequences. Analysis The historical perspective confirms that sustainable yield is indeed an evolving concepts. In assessing groundwater sustainability, issues of surface water hydrology, ecology, and water resources technology are seen to be intertwined with the issue of social license. The concepts may be summarized as follows:

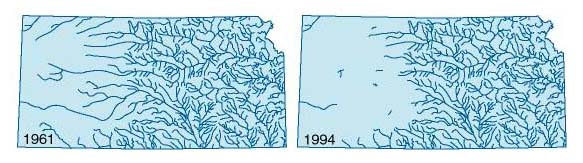

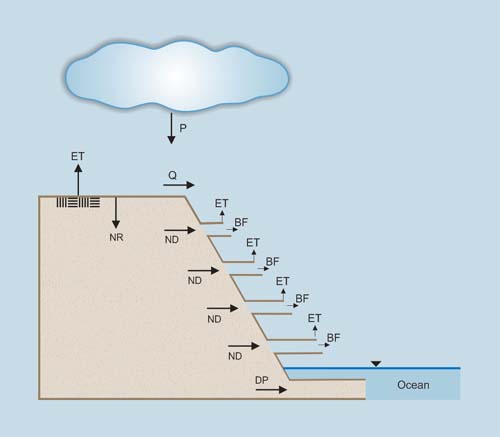

The solution is to focus on a water balance that considers both surface water and ground water. Precipitation, the source of all ground water, separates into several components as follows: (1) return to the atmosphere via evaporation; (2) return to the atmosphere via evapotranspiration; (3) return to the ocean through direct runoff; (4) return to the ocean through baseflow and, subsequently, streamflow; (5) return to the ocean through deep percolation. Of the five components of precipitation, only the third (direct runoff) is totally independent of ground water. Fractions of evaporation and evapotranspiration may [originate and] be part of ground water. All baseflow originates and is part of ground water. All deep percolation is part of ground water, but not part of streamflow. The components vary with climate, scale, and local and regional geologic and hydrogeologic conditions. For the sake of reference, on a global annual basis, evaporation and evapotranspiration is 58% of precipitation, streamflow is 40% (direct runoff is 28% and baseflow 12%), and deep percolation is 2% (World Water Balance 1978; L'vovich 1979). Like precipitation, natural recharge separates into several components as follows: (1) return to the atmosphere via evaporation from bare soil; (2) return to the atmosphere via evaporation from bodies of water; (3) return to the atmosphere via evapotranspiration from vegetation, both natural (ecosystems) and human induced (agriculture); (4) return to the ocean through the baseflow of streams and rivers; and (5) return to the ocean through deep percolation. Of the five components of natural recharge, only No. 5 (deep percolation) is totally independent of the continental surface waters; therefore, it may be a potential candidate for capture by groundwater systems. Thus, on a global annual basis, up to 2% of precipitation may be potentially tapped by groundwater systems with minimum encroachment on established surface water rights. In practice, specific values of deep percolation would have to be established on a local, subregional, or regional basis. For groundwater basins lying in close proximity to the ocean, the capture of all or fractions of deep percolation should be examined carefully because of the possibility of salt-water intrusion. Of the remaining four components (Nos. 1 to 4), it may be readily argued that all or fractions of No. 1 (evaporation from bare soil) may be also a candidate for capture by groundwater systems. It is more difficult to argue in favor of capturing all or fractions of No. 2 (evaporation from water bodies) and No. 3 (evapotranspiration from vegetation). It is most difficult to argue in favor of capturing all or fractions of No. 4 (baseflow). In general, a detailed water balance and related interdisciplinary studies are required to determine whether it is socially acceptable to set values of sustainable yield to encompass not only fractions of component No. 5 (deep percolation), but also appropriate fractions of components 1, 2, 3, and 4. Essentially, the goal is to be able to determine an appropriate yield-to-recharge percentage, and that this percentage be accepted as a reasonable compromise between conflicting interests. What are typical values of the yield-to-recharge percentage? In this connection, it is instructive to examine examples of usage-to-recharge percentages. Solley et al. (1998) have estimated that the pumpage of fresh ground water in the United States in 1995 was approximately 77 billion gallons per day, which is 8.6% of the estimated more than 891 billion gallons per day of natural recharge to the Nation's groundwater systems (Nace 1960; Alley et al. 1999). Limited experience suggests that workable yield-to-recharge percentages are likely to be somewhat higher (Miles and Chambet 1995; Prudic and Herman 1996; Hahn et al. 1997). Case Studies

Recent experience in Nevada suggests that groundwater modeling can be effectively used for a long term assessment of the

water balance (Prudic and Herman 1996). Paradise valley is within the watershed of the Humboldt river, in Humboldt County,

Nevada. According to a calibrated pre-development steady-state groundwater model, natural inflow to, and outflow from, the

Paradise valley groundwater system was 91 Miles and Chambet (1995) assumed that there is an acceptable level to which outflows from an aquifer (baseflow) may be allowed to fall, following groundwater pumping. The acceptable level of baseflow reduction is then linked to the expected drought duration and used to calculate a yield-to-recharge ratio. The latter is expressed as a function of dimensionless aquifer diffusivity, with the level of baseflow reduction as a curve parameter. The method was applied to the catchment of the River Worfe, in Wales, Great Britain, and its underlying Bunter Sandstone aquifer. Calculated yield-to-recharge percentages, when baseflow was reduced to zero, which is clearly the least conservative assumption, varied in the range 50-78%.

In Cheju Island, Korea, the mean annual precipitation is 1872 mm, which amounts to 3.39 km3 yr-1.

Of this volume, 19% (0.64 Sophocleous (2000a, 2000b) has provided extensive documentation on the Kansas experience in groundwater management. In 1972, the Kansas Legislature passed the Kansas Groundwater Act authorizing the formation of local groundwater management districts (GMDs) to help control and direct the development and use of groundwater resources. In the mid 1970s, the Central Kansas GMDs 2 and 5 adopted a safe yield policy of balancing groundwater pumping with the average annual recharge. This policy slowed down the rate of groundwater depletion, but it did not stop it. Following the establishment of the safe yield policy, both GMD 2 and GMD 5 experienced groundwater level declines of more than 6 m in parts of their districts. In some areas, the depletion amounted to 60 m, reducing by more that 50% the saturated aquifer thickness. As a result of these declines, streamflows in Western and Central Kansas have been decreasing and riparian vegetation has been progressively degrading, with numerous dead cottonwood and poplar trees visible around the countryside. In response to these streamflow declines, in 1984 the Kansas Legislature passed the minimum instream flow law, which requires that minimum desirable streamflows (MDS) be maintained in different streams in Kansas (Sophocleous 2000a). With continuing declines in groundwater levels and streamflow during the 1980s, the Kansas GMDs 2 and 5 moved in 1994 toward the conjunctive management of stream-aquifer systems, by amending their safe yield policies to include baseflow when evaluating a groundwater application. Baseflow is estimated as the streamflow that is exceeded 90% of the time on a monthly basis. Significantly, while GMD 2 continues to refer to their evolving policies with the term safe yield, GMD 5 has opted to use instead the term sustainable yield (Sophocleous 2000b).

Maimone (2004) has described the case of Nassau County, New York, as a tradeoff between

groundwater quality and surface-water quantity. Nassau County has an area of about 500 km2 and a population of 1.3

million people, and is a moderately densely populated suburban county. In the 1970s and 1980s, with nitrate

concentrations in ground water increasing due to on-lot septic systems, a decision was made to install sewer lines in

90% of the county, with ocean outfalls used for treated sewage disposal. As a result, the consumptive use of ground

water (water pumped and not returned through recharge) rose to 250

In Suffolk County, New York, with an area somewhat greater than 2000 km2 and a population slightly greater than Nassau County,

sewering accounts for less than 70 The Chester County Water Resource Authority, in Pennsylvania, has recently developed a comprehensive water resources plan for its watersheds (Chester County Water Resources Authority 2002). Significantly, stream baseflow was selected as the standard against which to measure groundwater pumping. Accordingly, to protect stream baseflow, the regulation limited ground water withdrawals in the following categories:

The more conservative lower management target of 50%, applicable to first order streams and certain designated baseflow-sensitive subbasins, would protect half of the baaseflow or low flow that recurs instantaneously once every 25 years. In practice, this means using up to 50% of the 1-day 25-year low flow. The less conservative upper target of 100%, applicable to all other areas, would use up all the baseflow that recurs once every 25 years. The case studies described above enable the following conclusions:

Synthesis All groundwater reservoirs of economic importance are temporarily holding water in transit from a place of recharge to a place of discharge. Any amount of water extracted from the ground through pumping would have to be eventually replaced by the same amount coming from the surface waters. A pristine groundwater reservoir is in steady state, with inflows equal to ouflows. When a groundwater reservoir is full, it rejects all water, which has no choice but to augment the surface waters. Conversely, when a groundwater reservoir is not full, it can take more water, but it will discharge more water too, through natural discharge. The natural discharge supports riparian, wetland, and other groundwater-dependent ecosystems, as well as the baseflow of streams and rivers. All pumping comes from capture, and all capture is due to pumping. The greater the intensity of pumping, the greater the capture. Capture comes from decreases in natural discharge and increases in recharge, the latter coming either from increased ground surface recharge or from the surrounding areas. In depletion cases, capture is augmented with decreased storage, i.e., with a permanent lowering of the water table. The water that seeps below the ground surface can follow one of three paths: (1) return to the atmosphere via evaporation and evapotranspiration (2) return to the ocean via baseflow and subsequent streamflow; or (3) return to the ocean through deep percolation. Of these three, only deep percolation is completely independent of the continental surface waters. Therefore, it is the only component of precipitation (or recharge) that may be potentially subject to sequestering (capture) by pumping. Studies are needed on a local, subregional, and regional basis to determine deep percolation as a percentage of precipitation, or alternatively, as a percentage of recharge. For groundwater basins in close proximity to the ocean, the possibility of salt-water intrusion must be examined carefully. A groundwater reservoir is essentially a leaky, porous natural geologic container (Fig. 3). In nature, precipitation P separates into direct runoff Q, evaporation and evapotranspiration ET, and natural recharge NR. All natural recharge eventually flows out as either natural discharge ND or deep percolation DP, at various spatial scales, from small to large watersheds. Natural discharge can return to the atmosphere via evaporation and evapotranspiration ET, or to the ocean via baseflow BF. The deeper the ground water, the larger the spatial scale of natural discharge, from the local to the regional scale.

|

Fig. 3 Geometric model of a groundwater reservoir.

|

The portion of natural discharge that returns to the atmosphere via evaporation and evapotranspiration is mostly already committed. Only a small fraction of it (the water that evaporates directly from the ground) may be subject to capture, if deemed necessary to satisfy socioeconomic needs. The case for the sequestration of the other two fractions (the evaporation from bodies of water and the evapotranspiration from vegetation) is usually less defensible. Sustainability studies will require a balance of the entire hydrologic system, not just of the aquifer. A careful accounting of the fate of all water is essential for effective management. Aboveground consumption is the key to sustainable management, and not necessarily the rate at which groundwater is pumped (Kendy 2003). Sustainable yield does not depend on the size, depth, or hydrogeologic characteristics of the aquifer. Current practice notwithstanding, sustainable yield does not depend on the aquifer's natural recharge, because the natural recharge has already been appropriated by the natural discharge (Sophocleous 2000a). Sustainable yield depends on the amount of capture, and whether this amount is socially acceptable as a reasonable compromise between little or no use, on one extreme, and sequestration of all natural discharge, on the other (Alley et al. 1999). Sustainable yield is seen to be a moving target, to be determined after a judicious study and appraisal of all issues regarding groundwater utilization (Maimone 2004). These include hydrogeology, hydrology, ecology, climatology, social and economic development, and the related institutional and legal aspects, to name the most relevant. In practice, sustainable yield may be taken as a suitable percentage of precipitation. A reasonably conservative estimate would take the entire deep percolation amount as sustainable yield. On a global basis, deep percolation amounts to about 2% of precipitation. In the absence of basin-specific studies, this figure may be used as a point-of-start on which to base sustainable yield assessments. A fraction of evaporation and evapotranspiration (ET) is seen to be part of discharge (ND), which originates in recharge (NR). A detailed water balance is required to evaluate the components of precipitation and recharge, so that the fractions of deep percolation, evaporation, evapotranspiration and baseflow that may be candidates for capture, can be ascertained. Sustainable yield can also be expressed as a percentage of recharge. Globally, if recharge can be assumed to be approximately 20% of precipitation, then deep percolation would be about 10% of recharge. Thus, a reasonably conservative estimate of sustainable yield would be 10% of recharge. Limited experience indicates that average values of this percentage may be around 40%, while less conservative percentages may exceed 70% (Miles and Chambet 1995; Hahn et al. 1997). The current concept of sustainable yield represents a compromise between theory and practice. In theory, a reasonably conservative estimate of sustainable yield would be about 10% of recharge. In practice, values higher than 10% may reflect the need to consider other factors besides conservation. Communities are beginning to consider baseflow conservation as the standard against which to measure groundwater pumping and, therefore, sustainable yield (Maimone 2004). Compromises may be reached by specifying the maintenance of minimum low flows of selected durations and frequencies. Ultimately, baseflow conservation may be the only practical way of assuring that groundwater capture is reasonably regulated and, therefore, does not end up sequestering the entire natural discharge. In theory, whoever owns the natural discharge owns the groundwater that feeds that natural discharge. This natural discharge can be shown to provide natural and socioeconomic services. Natural services are associated with the maintenance of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems that rely on the natural discharge. These ecosystems may comprise, for example, wetlands, riparian species, and minimum instream flows to sustain fisheries and wildlife. Socioeconomic services are associated with water rights that may have been already appropriated to individual users or social entities. In practice, it does not appear viable, in all cases, to disallow groundwater use on account that the entire natural discharge may have been already appropriated. Experience shows that reasonable compromises may be established on a case-by-case basis. In this context, it is extremely important to strive toward a holistic approach to sustainability. This approach considers the hydrogeological, hydrological, ecological, socioeconomic, technological, cultural, institutional and legal aspects, in a seamless fashion, seeking to establish a reasonable compromise between conflicting interests. For the most part, groundwater depletion may be deemed unacceptable, but a reasonable amount of steady capture may be acceptable if a consensus can be achieved as to its size, with full recognition and, consequently a thorough evaluation, of the tradeoffs. Groundwater sustainability may be enhanced by increasing recharge in three ways: (1) capturing rejected recharge; (2) encouraging clean artificial recharge, and (3) limiting negative artificial recharge. The greater the amount of capture coming from rejected recharge, the more sustainability is assured. Likewise, the greater the clean artificial discharge, the more sustainability is assured. Limiting negative artificial recharge, to the extent possible, would go a long way toward assuring sustainability. Conclusions The issue of how much to pump in a sustainable context is shown to have no simple answer. The traditional concept of safe yield, which equates safe yield with natural recharge, is flawed and has been widely discredited. Since 1987, the concept of sustainable yield has emerged, seeking to provide a reasonable compromise between the rights of established ground water users, and the rights of downstream ecosystems and surface water users to the natural discharge which is sustained by that ground water. The ideal solution appears to be to conserve all ground water, excluding all or suitable fractions of deep percolation, for the benefit of the surface waters. However, this solution may prove to be too harsh, and probably socioeconomically not viable in places where ground water usage has become, over the years, a way of life. It is clear that sustainable yield can no longer be taken as equal to natural recharge. A suitable compromise may be to consider sustainable yield as a fraction of natural recharge, provided a thorough evaluation is made of the tradeoffs, including the hydrological and ecological impacts of groundwater development. Baseflow, more properly baseflow conservation, is emerging as the standard against which groundwater pumping will be increasingly measured in the future. In the absence of detailed holistic studies, a reference value of sustainable yield may be taken as all, or a suitable fraction of, the global average for deep percolation, estimated as 2% of precipitation. Detailed local and regional studies will determine whether this value may be increased on a case-by-case basis to reflect one or more of the following: (1) an improved understanding of the components of the water balance; (2) a workable compromise between conflicting socioeconomic interests; or (3) the choice of a less conservative approach to resource management. Sustainability goes hand-in-hand with conservation; the more conservative the proposed or adopted policy, the more sustainable it is likely to be. Acknowledgments This study was made possible with the support of the people of the communities of Boulevard and Campo, in eastern San Diego County, California. References Alley, W. M., T. E. Reilly, and. O. E. Franke. 1999. Sustainability of groundwater resources. U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1186, Denver, Colorado, 79 p. Alley, W. M., and S. A. Leake. 2004. The journey from safe yield to sustainability. Ground Water, Vol. 42, No.1, January-February, 12-16. Chester County Water Resources Authority. 2002. Watersheds: An integrated water resources plan for Chester County, Pennsylvania, and its watersheds. Adopted September 17, 2002, 240 p. Hahn, J., Y. Lee, N. Kim, C. Hahn, and S. Lee. 1997. The groundwater resources and sustainable yield of Cheju volcanic island, Korea. Environmental Geology, 33(1), December, 43-52. Hardin, G. 1968. The Tragedy of the Commons. Science, Vol. 162, 1143-1148. Kazmann, R. G. 1956. "Safe yield" in ground water development: Reality of illusion? Journal of the Irrigation and Drainage Division, American Society of Civil Engineers, Vol. 82, No. IR3, November, Paper 1103. Kendy, E. 2003. The false promise of sustainable pumping rates. Ground Water, Vol. 41, No.1, January-February, 2-4. Lee, C. H. 1915. The determination of safe yield of underground reservoirs of the closed-basin type. Transactions, American Society of Civil Engineers, Vol. LXXVIII, Paper No. 1315, 148-218. L'vovich, M. I. 1979. World water resources and their future. Translation of the original Russian edition (1974), American Geophysical Union, Washington, D.C. Maimone, M. 2004. Defining and managing sustainable yield. Ground Water, Vol. 42, No.6, November-December, 809-814. Miles, J. C., and P. D. Chambet. 1995. Safe yield of aquifers. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management, American Society of Civil Engineers, Vol. 121, No. 1, January/February, Paper No. 5381, 1-8. Nace, R. L.. 1960. Water management, agriculture, and groundwater supplies. U.S. Geological Survey Circular 415, Denver, Colorado, 12 p. Prudic, D. E., and M. E. Herman. 1996. Ground-water flow and simulated effects of development in Paradise Valley, a basin tributary to the Humboldt River, in Humboldt County, Nevada. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1409-F. Seward, P., Y. Xu, and L. Brendock. 2006. Sustainable groundwater use, the capture principle, and adaptive management. Water SA, Vol. 32, No. 4, October, 473-482. Solley, W. B., R. R. Pierce, and H. A. Perlman. 1998. Estimated use of water in the United States in 1995. U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1200, Denver, Colorado, 71 p. Sophocleous, M. 1997. Managing water resources systems: Why "safe yield" is not sustainable. Ground Water, Vol. 35, No.4, July-August, 561. Sophocleous, M. 2000a. From safe yield to sustainable development of water resources - The Kansas experience. Journal of Hydrology, Volume 235, Issues 1-2, August, 27-43. Sophocleous, M. 2000b. The origin and evolution of safe-yield policies in the Kansas Groundwater Management Districts. Natural Resources Research, Vol. 9, No. 2, 99-110. Theis, C. V. 1940. The source of water derived from wells: Essential factors controlling the response of an aquifer to development. Civil Engineering, Vol 10, No. 5, May, 277-280. World Commission on Environment and Development (The Brundtland Commission). 1987. Our Common Future. The United Nations, New York. World Water Balance and Water Resources of the Earth. 1978. U.S.S.R. Committee for the International Hydrological Decade, UNESCO, Paris, France. __________________________ 1Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, San Diego State University, San Diego, California USA; 1-619-594-4029; E-mail: [email protected]; URL: http://ponce.sdsu.edu

|